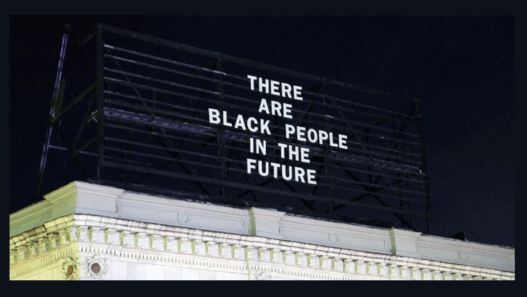

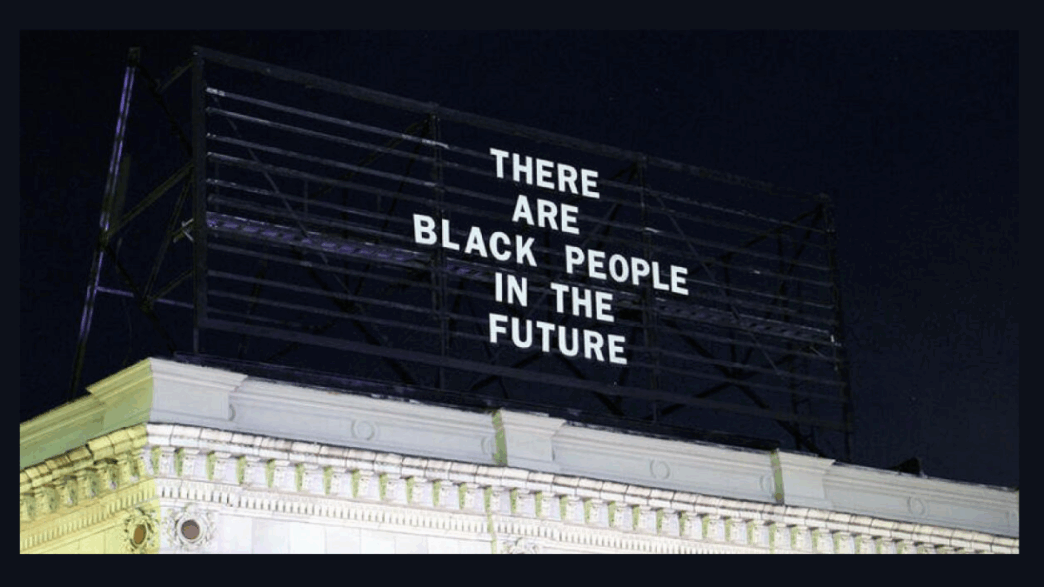

Who knew that a billboard proclaiming that “There Are Black People In The Future” would get many colonizers upset? Perhaps, the idea of Black people in the future brings them fear. Fear that they might not be able to experience that future themselves? Who knows, but the billboard was taken down because colonizers were offended but then they released a statement.

As reported by Artnet:

The artist, But she may not have been prepared for the backlash to the backlash. This morning in a separate statement, she said that in the previous 24 hours, the company had “received a number of emails from people who said they are not offended by the sign and are saddened by its removal. They far outnumber the people who originally approached us about being offended.”

According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Picker was more candid in a message to Jon Rubin, the founder and curator of The Last Billboard project. She told him that her inbox had been flooded with messages accusing her of being a racist. “So here we are,” she wrote to him, according to the newspaper. “Art has caused friction. Perhaps that’s what you wanted but it shouldn’t be aimed at me.”

Indeed, opposition to the work’s removal mounted after Rubin posted a statement online about the billboard’s removal on April 3. He noted that Wormsley’s text is a natural outgrowth of her work, which is inspired in part by Afrofuturism. “I believe in the power, poetry, and relevance of Alisha’s text and see absolutely no reason it should have been taken down,” Rubin said.

He added: “I find it tragically ironic, given East Liberty’s history and recent gentrification, that a text by an African American artist affirming a place in the future for black people is seen as unacceptable in the present.” He declined to comment further when reached by artnet News.

Picker, the landlord, maintains she was within her rights to ask for the Wormsley’s message to be removed because the lease agreement states that the billboard cannot present messages “that are distasteful, offensive, erotic, [or] political.” She acknowledged that Rubin had erected works in the past without seeking formal approval, but said that in the future, the Last Billboard project must follow the formal process outlined in the lease agreement.

Ironically, Wormsley has been celebrated specifically for her work with public art in the past. In 2015, she accepted the Pittsburgh mayor’s award for public art for her involvement with the Homewood Artist Residency, a program that brings artists to the city’s Homewood neighborhood to create a project inspired by the community.

In a statement posted on her website today, Wormsley said she was “deeply saddened” by the work’s removal but “comforted by how my Pittsburgh has stood up.”

She added: “I think we all know what it is to have discomfort. Let’s begin to work on methods to constructively investigate that discomfort without using power over anyone or anything else.” She also encouraged others to make work out of the phrase. “This text is a sentence I do not own, it is for anyone who wants to use it,” she said. “Please. Take it.”

On April 18, the artist is scheduled to participate in a public panel discussion about the billboard and broader questions about how communities ought to navigate art in public spaces.

Here is Wormesley describing her project and movement “There Are Black People In The Future”:

While in residence in the Homewood Artist Residency, supported by the Andy Warhol Museum, I developed a series of montage driven short films titled, Children of NAN. From this series came the title of the current project, “There Are Black People In The Future.” Working in Homewood, I started connecting my work with the community by investigating the joys, triumphs, and LEGACY of this region. I also began to uncover and directly connect the developments in my studio with the challenges, fabricated perceptions, stereotypical prophecies, mental madness, localized mythology, and institutional obstacles readily occurring outside my window. With a collaborative spirit, I began collecting discarded and found objects, some, donated by students and elders in the community. The ritualistic actions of casting and printing on these objects that ensued was directly entwined with Homewood’s existence and survival. And mine…

The landlord admits that the people who complained didn’t outnumber the people who supported the public, so why did she take it down in the first place? It’s currently back up, but removing public art over a few sensitive people’s feelings defeats the purpose of the message.

Mad ethnic right now...